By Leah Kivivali, La Trobe University, Australia

Inflammation. When most of us think of inflammation, we probably think about a swollen joint or swelling around a wound, but can inflammation also affect our brains. Ultimately, inflammation is good. It’s the process whereby our body eradicates invading pathogens and helps us fight disease. However, inflammation can turn bad when the signalling to turn it off after the threat has gone doesn’t work.

Inflammation and depression

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, activated by inflammatory compounds called cytokines, works to send signals to turn off inflammation.

If this negative feedback loop is broken and the HPA axis fails to shut off after immune response, it can stimulate the continued release of cytokines. Whilst these inflammatory processes are critically important, over activated, or long-lasting inflammatory processes can be harmful.

There is an established link between low grade, chronic inflammation and mental health. Further, our stress hormone, cortisol, released during the activation of the HPA axis, is commonly dysfunctional in depression. This research has led to the cytokine theory of depression.

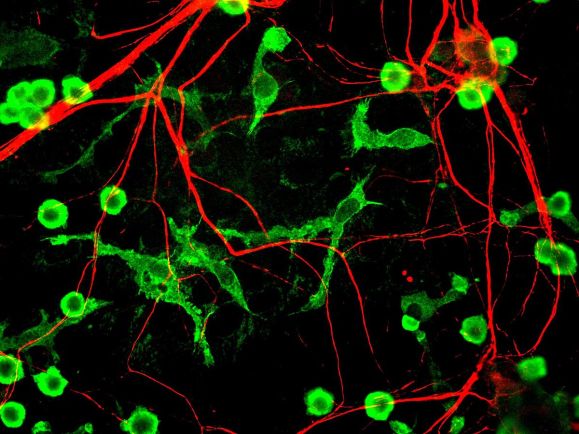

The dysfunction of the resident immune cell in the brain, microglia, might be at the heart of this increased brain inflammation in depression, otherwise known as neuroinflammation. In the brain, microglia act as a first line defence if they sense something is amiss. This involves coordinating the release of cytokines. Once again, this is a very important and tightly orchestrated process; but, if for some reason the microglia are unable to shut down after the threat has subsided, then chronic, low levels of neuroinflammation may remain.

Treating inflammation in depression

Causes of depression are many and varied: stressful and traumatic events, biological chemical imbalance, hormones, genetics and aging to name a few. The most common medical treatment for depression is taking drugs to increase the levels of serotonin in the brain, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

However, these drugs don’t work for everyone with clinical depression, so great effort in the research community has been invested in figuring out what else might work for these people. An intriguing line of investigation has looked the role of the immune system in depression and how anti-inflammatory drugs may be used in complement with other, traditional anti-depressant treatments, such as SSRIs, to reduce depressive symptomology.

Some of the first evidence came from studies that found patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis, inflammatory diseases, given common anti-inflammatory drugs demonstrated improvements in their mental state. This research led to direct comparisons of anti-inflammatory drugs for patients with depression, which has so far demonstrated promising results when combined with more traditional medical treatments such as SSRIs.

Take home message

Depression is a heterogeneous disease; there is no one cause, and no one effective treatment for all. This story is not isolated to depression, we are learning more and more about how inflammation in the brain can be a leading contributor in developing a whole host of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease.

A lot of this research is still emerging and more wide-scale, randomised control trials, as well as pre-clinical research, is needed.

However, on a basic level, if inflammation in our brains is in part contributing to depression, then it makes sense to treat this as we would other inflammation in our bodies. This is a simplistic view, however, with the progression of scientific findings and medical treatments, it makes it possible to understand diseases from different points of view, and therefore, try and treat them with different strategies.

About me

About me

I am a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in neuroscience at La Trobe University in Melbourne, where I obtained a PhD in neuroscience. I have wide and varied experience ranging from bench science and neuroscience to public health, mental health, epidemiology and rare diseases. I am the author of the Woman in Science blog and you can also find me on Twitter @WomanScience and on Instagram @woman_science.

This post is the third in our inflammation series. The first and second posts – Fibrosis: an overlooked companion of inflammation by Conor Sugden and Can your diet reduce inflammation? by Richard Miller – were published in September. If you are interested in reading more on this topic, you can also check out the August issue of The Biochemist magazine on the theme of inflammation.

One thought on “Resident evil: inflammation and depression”